Dizziness and Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

What is Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)?

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is an inner ear problem that results in short lasting, but severe, room-spinning vertigo. Its name, BPPV, indicates that it is benign, or not a very serious or progressive condition; paroxysmal, meaning sudden and unpredictable in onset; positional, because it comes about with a change in head position; and vertigo, causing a sense of room-spinning or whirling, often expressed as "dizziness." Although called benign, those who suffer from this distressing and incapacitating condition do not trivialize BPPV.

What are the symptoms?

This condition often begins following head trauma or a severe cold. It can also arise simply as part of the aging process. It starts suddenly and is usually first noticed in bed, when waking from sleep. Any turn of the head seems to bring on violent but brief bursts of dizziness. Patients often describe the occurrence of vertigo with tilting of the head, looking up or down (so called "top-shelf vertigo"), or rolling over in bed. It is not unusual for nausea and vomiting to accompany the vertigo. Even if a spell is brief, a feeling of queasiness may last several minutes or even hours.

There is no new hearing loss or severe ringing associated with these attacks, which helps to distinguish BPPV from other inner ear conditions.

What causes BPPV?

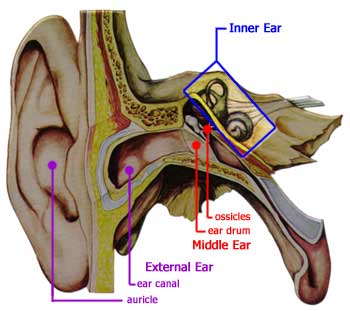

To understand the cause of BPPV it is helpful to understand how the inner ear works. The human ear is divided into three parts: the external, middle, and inner ear.

The external ear consists of the part of the ear you can see (the auricle) and the ear canal.

The middle ear includes the eardrum (tympanic membrane) and the three bones, or ossicles, of the middle ear, the malleus ("hammer"), the incus ("anvil"), and the stapes ("stirrup").

The inner ear is a fluid-filled series of chambers. One of these chambers, the cochlea, is responsible for converting sound vibrations into nerve impulses. It is these nerve impulses that the human brain interprets as sound and what we call "hearing."

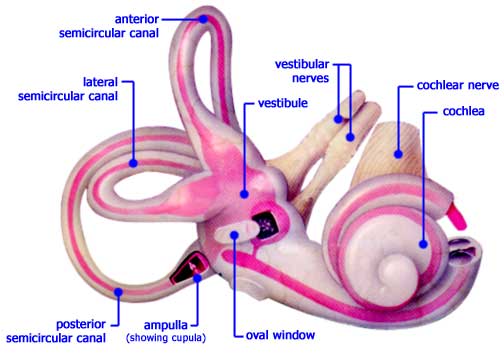

The inner ear also contains 3 semicircular canals which are responsible, in part, for sensing movement and maintaining balance. As you can see, these 3 canals (named anterior, lateral, and posterior) are oriented at roughly right angles to one another. The movement of the fluid within these canals allows the brain to sense rotation of the head through all three directions in space (e.g. left-right, forward-back, and up-down). All 3 canals are connected to a large chamber, called the vestibule.

It has been discovered that the probable cause of BPPV is dislodgement of small calcium carbonate crystals that float through the inner ear fluid and strike against sensitive nerve endings (the cupula) within the balance apparatus at the end of each semicircular canal (the ampulla). (Another name for BPPV is cupulolithiasis, meaning "rocks in the cupula".)

These crystals, known as otoconia, usually dissolve or fall back into the vestibule within several weeks, and no longer cause any symptoms. However, in some patients, these crystals become trapped in the fluid of the balance chamber and periodically cause symptoms, as gravity and head movements cause them to repeatedly strike against the cupula. In these patients, the symptoms may not subside and they become severely incapacitated.

Interestingly, the loose otoconia tend to settle preferentially within the posterior semicircular canal. As you can imagine from looking at the illustration above, this is because the posterior canal hangs down like the water trap in a drain pipe, allowing the crystals to settle in the bottom of the canal.

How is BPPV diagnosed?

The most important means for diagnosing this condition is the physical examination and history of the patient. A patient with dizziness or vertigo without hearing problems suggests the diagnosis of BPPV. A normal ear exam, audiogram, and neurological exam are expected. A simple positional test, performed in the doctor's office, is usually all that is needed to confirm the diagnosis of BPPV.

One such test is the Dix-Hallpike test. First, the patient is positioned on the examining table, seated upright. Then the examiner brings the patient's head down over the edge of the table and turns the head to one side. If the patient has BPPV, the examiner will witness a characteristic movement of the eyes, call nystagmus, that begins after a few seconds. If the nystagmus is seen and the patient becomes dizzy, then the ear which is pointing toward the floor is the one with the loose otoconia. If no nystagmus is seen the examiner will repeat the test, this time turning the head to the opposite side, thus testing the other ear.

This nystagmus and perception of vertigo will slow down and cease after 15 to 20 seconds. If the head is not moved, no further symptoms will occur. When the patient sits back up, the dizziness will recur, but for a shorter period of time. Lying down on the opposite side will not cause the vertigo. Occasionally, in order to confirm the extent of the inner ear dysfunction, an electronystagmogram (ENG) will be ordered.

What are the treatments for BPPV?

Once tests have confirmed the diagnosis of BPPV and the affected ear, patients are instructed to avoid lying down on the affected side. Usually, medications like Antivert (meclizine), Dramamine, Valium, or Phenergan are not recommended because they cause sedation. By carefully avoiding the provocative position, patients can usually avoid bringing about the symptoms. If left untreated, the condition usually clears within several weeks.

The Epley or Semont Maneuver

Recently, researchers have found that a simple and well-tolerated physical therapy technique performed in the office can relieve the vertigo in a high percentage of patients. The Otolith Repositioning Procedure of Semont and Epley has become well accepted and is based on using gravity to move the crystals away from the nerve endings into an area of the inner ear that won’t cause any problems. Sometimes, a vibrator is placed on the mastoid to "liberate" the particles and improve the procedure's success.

Watch the animation and notice that as the patient is moved into the various positions of the maneuver, the posterior semicircular canal is rotated in such a way as to deposit the displaced otoconia back into the vestibule where they can do no further harm.

In our experience, approximately 75% of patients are cured with one maneuver. This percentage increases with repeated treatments. Following the maneuver, patients must not lie flat for 48 hours, meaning they should sleep in a recliner or propped up on pillows. Also, after 48 hours, patients should not lay down on the affected ear for at least one week following the treatment. Even tying shoes or bending over should be avoided during this week. These instructions help prevent the crystals from falling back into the balance chamber.

Surgical Treatments

Rarely, when time and the otolith repositioning techniques have failed, severe cases may eventually require surgical intervention. The following are of several procedures which may be considered.

Singular Neurectomy (or Posterior Ampullar Nerve Section)

A tiny branch of the balance nerve travels through a bony canal before it reaches the nerve endings of the balance canal. The goal of this surgery is to expose the canal through the ear and to cut this tiny nerve. After this is done, if the crystals strike the nerve endings, the patient has no symptoms because this information no longer reaches the brain. In experienced hands, this surgery is safe and relieves the symptoms permanently. In a small percentage of cases, the nerve is located in an unreachable spot and cannot be safely cut. In these cases, no improvement is achieved. In a few patients, hearing loss, tinnitus, and dizziness can result from the surgery.

Posterior Canal Plugging Procedure

This is a recently developed procedure that has nearly replaced the singular neurectomy due to its ease and effectiveness. In this procedure, a mastoidectomy is performed through an incision made behind the ear. The balance center is then uncovered and the posterior semicircular canal is opened, exposing the delicate membranous channel in which the crystalline debris is floating. The canal is then gently, but firmly packed off with tissue so the debris can no longer move within the canal and strike against the nerve endings. The canal is then sealed and the incision closed.

Most patients will be somewhat dizzy the first night after this surgery, so a one-night hospital stay is advised. The patient returns in one week for suture removal. Because of blood and swelling, hearing loss and some dizziness may last several weeks. Medication is prescribed to minimize this and prevent complications. The acute vertigo from BPPV is cured in the majority of cases. The exact percentage of patients with some permanent hearing loss has not yet been firmly established. However, it has been reported to be less than 20% in early studies.

Vestibular Nerve Section (or Neurectomy)

In some cases, when positional vertigo is quite severe and hearing is still normal, testing reveals that this is not due to crystalline debris floating in the canal, but due to a severely damaged balance nerve. In such cases, the previous two procedures would not relieve the symptoms. Instead, the entire balance nerve is cut to prevent its distorted information from reaching the brain. In successful cases, after an initial period of several weeks, the dizziness gradually disappears. In addition, no future vertigo can occur from that diseased ear. For this operation, a neurosurgeon exposes the nerve as it crosses from the ear to the brain, then sections the nerve under direct vision with an operating microscope. Both the hearing nerve and facial nerve are monitored to prevent their inadvertent injury. In some cases, high frequency hearing loss and can occur because the balance nerve fibers (the vestibular nerve) and hearing fibers (the cochlear nerve) mix togther along the borders of the nerves.

Several days of hospitalization is customary following this procedure. Risks include hearing loss, tinnitus, facial nerve weakness, spinal fluid leakage, and meningitis. Although rare, these serious complications are important to recognize and acknowledge prior to proceeding with surgery.

Comment

No patient with disabling vertigo should suffer needlessly. If dizziness does not disappear over time with medication or with the physical therapy techniques described above, surgical therapy may be an option and should be discussed with your physician.

Notice

This information should be considered advisory in nature, and is not intended to be a substitution for evaluation and treatment by a licensed medical physician.